I chose not to attend my high school graduation ceremony, eager to head for Washington, D.C. where I had a summer job at the U. S. Senate. Though it was not a conscious decision at the time, it is clear now I was making a clean break with my past. I still think of the Rockies as home, but I never went back.

The separation was so complete I don’t remember – if I ever knew – who spoke to my graduating class. Instead, I marked my transition to college and the real world by reading essays from Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. This I remember clearly because one passage has always stayed with me and informed my life.

“As life is action and passion,” Holmes said, “it is required of a man that he should share the passion and action of his time, at peril of being judged not to have lived.”

Holmes’ observation came from the perspective of a civil war veteran injured three times in battle, a Harvard law professor, an Associate Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court for 30 years, and the oldest man to have ever served on the Court. Clearly, he had “walked the talk” and lived “fully.” I resolved to follow his example and embrace life.

A few years later, Doc English, my favorite teacher in law school, telegraphed another change of directions when he told me I probably would not make a good lawyer. “You are smart enough,” he said, “but you have an overdeveloped sense of justice.” It wasn’t meant as a compliment.

A Philadelphia lawyer with years of trial experience, Doc knew what he was talking about. It took me several years, including a year clerking with a law firm, to figure out he was right.

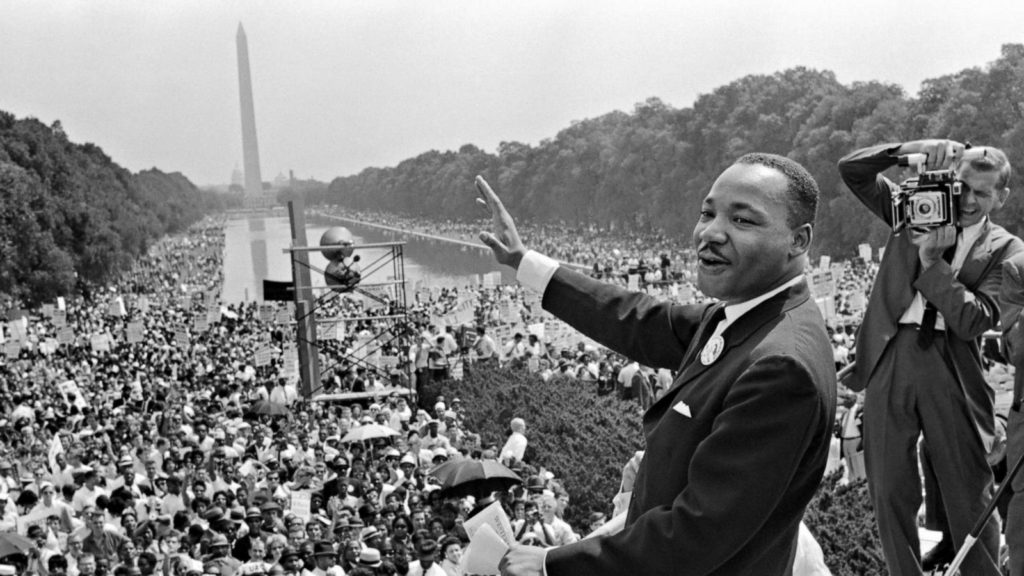

These things – my overdeveloped sense of justice and my desire to share in the action and passion of my time – led me to the Mall for the culmination of Dr. King’s March on Washington. The March on Washington was an unprecedented event. I wanted to show my support and be part of it.

The collective memory of this event focuses on Martin Luther King and his powerful words, but the moment wasn’t so defined at the time. King was one 18 speakers assembled for the occasion. All of them had something to say. It took history to show us King said it best.

My strongest memory of the moment, then and now, was not what the speakers had to say but the spirit of the occasion. Everyone there knew we were part of something important, something special and transcendent. The silent witness provided by the peaceful presence of so many people seeking justice spoke eloquently to the collective conscience of America, challenging us to live up our ideals.

The other indelible memory of the event was that it was permeated by fear. The potential for violence was almost palpable. Embedded in all that and perhaps feeding it was the unstated understanding that things were changing. For most people, particularly those who embraced this change, Dr. King was a hero, a prophet who signaled the direction. But some saw him differently.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was concerned enough by the march and Dr. King’s speech to step up their investigations of the Southern Christian Leadership Council and target King specifically as an enemy of the State. Speaking for the FBI, William C. Sullivan, head of Bureau’s intelligence operations, said, “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national security. Prominent politicians lead by Senator Strom Thurmond were quick to agree and launched an attack on the March, labeling it Communist.

This animosity did not go away quickly. When Dr. King was assassinated five years later, I was in law school. I had just met my favorite law professor and was about to be drafted for Vietnam. I watched as much of Washington went up in flames. I remember seeing the smoke from the steps of the Capitol. No one knew where it would lead or how it would end.

The elevator talk that day was all about Dr. King’s assassination and the tragic events it triggered. On one of my runs, a passenger heard the discussion and held back. After everyone else had cleared, he said, “It was about time somebody killed that son-of-a-bitch.” In shock, I watched Senator Strom Thurmond walk off my elevator and head down the hall.

This Senator went on to be re-elected repeatedly. They named roads and buildings after him. Near the end of his career the entire Senate turned out to honor him at a dinner in the Capitol where people who should have known better hailed him as one of the Senate’s icons.

When I look back over the course of what is now fifty years, I see a lot of change. But I know a lot remains. George Floyd made that clear.

If anything, we are more divided now than then. At times like this, at times of turmoil, risk, and division, it’s worth remembering that America is always a work in progress and we must recognize that in the battle between love and hate, apathy is the enemy.

If we truly want justice, if we want America to live up to her promise, if we stand with Dr. King and share his dream, we must make it happen. We must be the change we seek. Ultimately, America is and will always be whatever we are.

Thanks for sharing Bill. What an honor for you to have been in DC when Dr King spoke. How tragic it is that we are still fighting the same old fights. When will the people see everyone as a human being and respect that fact and see that so many of us are more alike than different in the way we care about the people in our world. K