History remembers John Adams as our first Vice President and America’s second president. He was on the drafting committee for the Declaration of Independence and argued eloquently for its passage. After July 4, 1776, Adams traveled to France, where he proved instrumental in winning French support for our war of independence.

So it is something more than ironic that twenty-five years later, Adams expressed concern for the viability of the Republic he helped create.

“Remember, democracy never lasts long,” he said, “it soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide.”

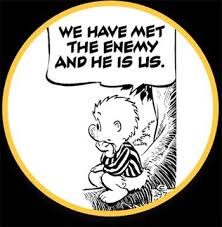

I find myself wondering if this process has begun. With every passing day, our country seems more divided and, as we all know, a house divided against itself cannot stand.

If we are honest, most of us will admit we have friends or relatives whose political persuasions trouble us. Many of us “shut down” conversations with these people because we are uncomfortable with where these conversations might lead. We find ourselves wondering how these good and decent people could be so lost and misguided without considering the possibility that they might be looking back through the looking glass and wondering the same thing about us.

Anyone bothering to check knows that those who watch Fox’s news, the largest cable outlet, get a totally different view of the world than those who watch MSNBC, the second largest network. These networks and others present alternative universes. They have alternative concerns, alternative facts, and alternative realities, while the algorithms that govern the social media we use are designed to tell us what we want hear, reinforce our pre-existing beliefs, and present nothing that challenges them. No wonder half the population thinks the other half is crazy.

At its core, this behavior reflects a loss of our sense of humility – the most misunderstood and least appreciated Biblical virtue. It symptom of a potentially lethal combination of ignorance and arrogance.

In 1944, Judge Learned Hand, the most distinguished jurist of his time, spoke to more than a million people gathered in Central park. The event was billed as “I Am An American Day” and focused on the 150,000 newly naturalized citizens included in the audience.

“We have gathered here to affirm a faith,” Hand told them, “a faith in a common purpose, a common conviction, a common devotion. Some of us have chosen America as the land of our adoption; the rest have come from those who did the same.

“What do we mean when we say that first of all we seek liberty? Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it. While it lies there, it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.

“And what is this liberty which must lie in the hearts of men and women? It is not the ruthless, the unbridled will; it is not freedom to do as one likes. That is the denial of liberty, and leads straight to its overthrow. A society in which men recognize no check upon their freedom soon becomes a society where freedom is the possession of only a savage few; as we have learned to our sorrow.

“What then is the spirit of liberty? I cannot define it; I can only tell you my own faith.

“The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the mind of other men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interests alongside its own without bias; the spirit of liberty remembers that not even a sparrow falls to earth unheeded; the spirit of liberty is the spirit of Him who, near two thousand years ago, taught mankind that lesson it has never learned but never quite forgotten; that there may be a kingdom where the least shall be heard and considered side by side with the greatest.”

That is our challenge. If our democracy is to survive, the spirit of liberty must be kept alive. It’s not something anyone can do for us. It is something we must do for ourselves.